Dear inflation, where to?

Issue #10

Hey people, welcome to the latest issue of Markets and Macros by TradingQnA. In today’s issue, we dive into the following topics:

Red hot inflation

IMFs gloomy outlook for the global economy

Summary of the RBI MPC meeting minutes and more...

Written by Abhinav, Bhuvan, Esha, Meher, Shruthi and Shubham

Weekly Market Wrap

A quick look at how the markets performed in the week:

🌶️ Red hot inflation

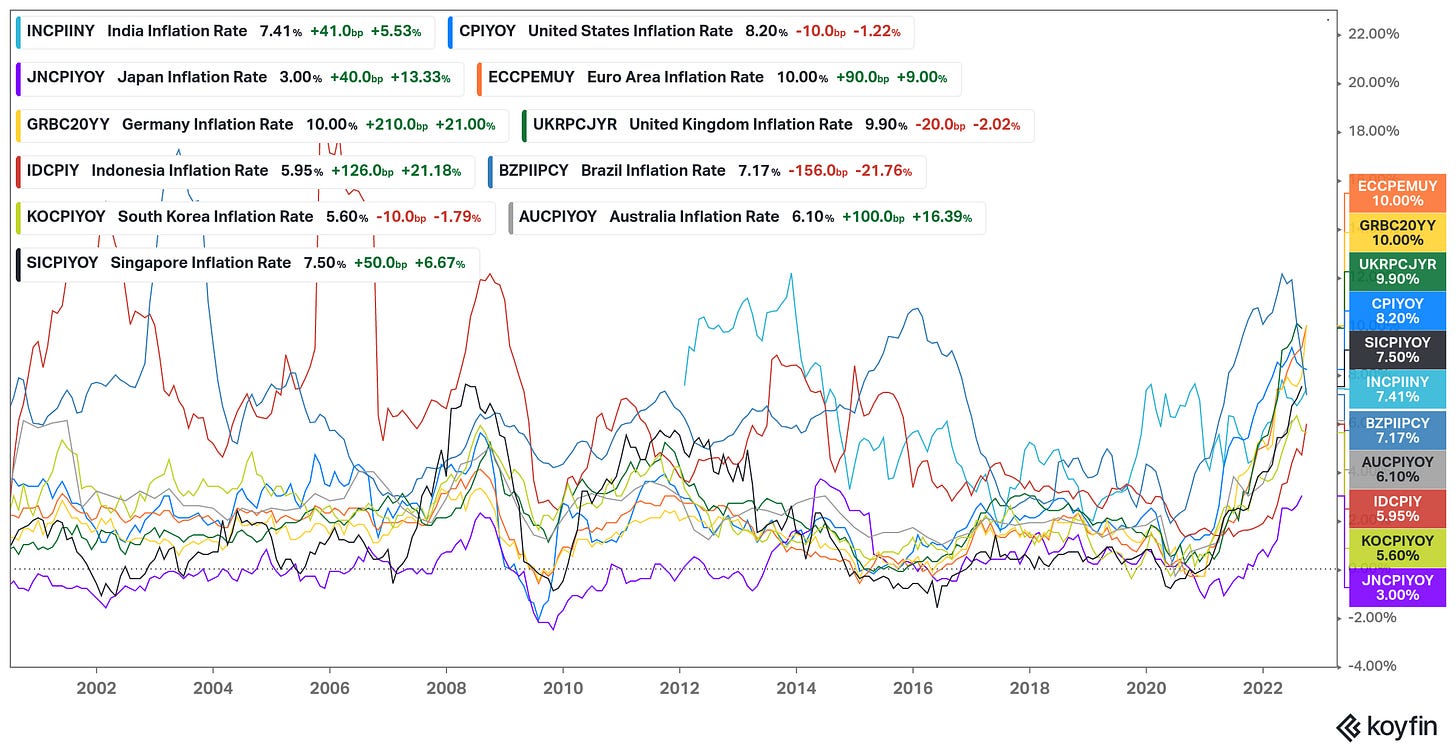

This week, there were inflation releases in India and the U.S., and both the prints came in hot. High inflation is nothing new for developing counties. For example, the average inflation in India since the 1960s has been about 7%.

But since the 1980s, inflation in the advanced economies has been on a gradual downtrend. An entire generation has never seen serious inflation until now, hence the freakout.

More broadly, you would’ve noticed that we’ve discussed inflation a lot in the previous editions of this newsletter. The reason is that inflation is a silent tax on everybody and everything. It affects everything from your wages to the returns on financial assets—it doesn’t discriminate between the rich and the poor. In fact, the people with the lowest income tend to be the most affected.

Prolonged periods of high inflation can also lead to political instability and revolutions.

First, a few highlights from this week’s Indian and U.S. inflation releases

India

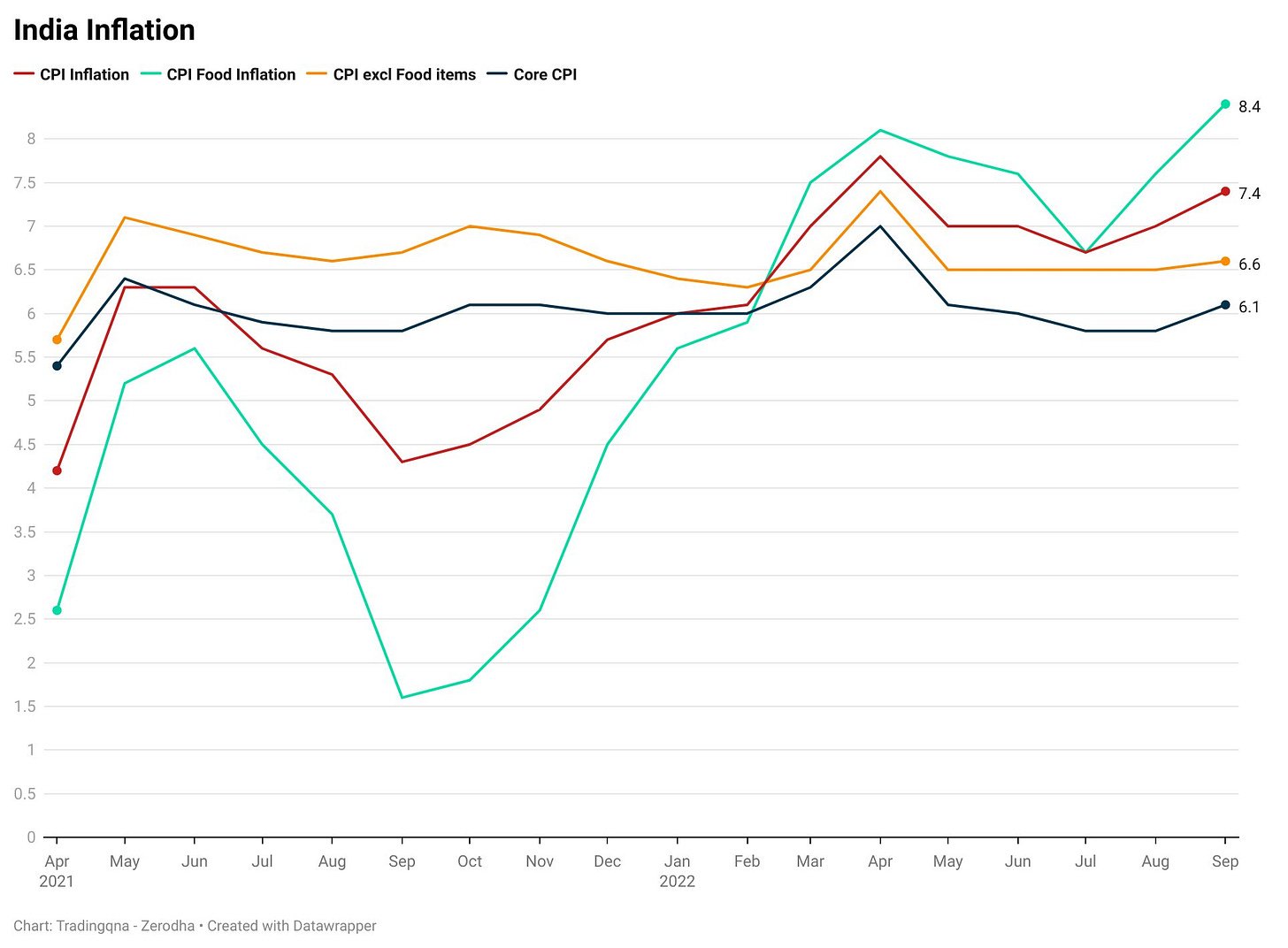

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rose to 7.4% YoY in September from 7% in August. CPI inflation has been above the 6% for eight consecutive months now. This is higher than the RBI tolerance limit of 6%.

Food inflation hit a 22-month high of 8.4% in September from 7.5% in August on the back of rising vegetables, cereals, pulses, and milk prices. This was one of the primary contributors to the rising inflation.

Core inflation, which is measured by excluding food and energy, also showed an uptick. This is a worrying sign because a rising core inflation number can often mean that stickier inflation components might remain elevated.

Domestic factors seem to be the driving factors behind the rise in inflation. Here’s a chart from Motilal Oswal, decomposing domestic and global inflation.

Based on the minutes of the last Monetary Policy Committee Meeting, there’s some difference over the path of further rate hikes.

Statement by Dr. Ashima Goyal

Although the large pandemic-time repo rate cut is reversed, we are not yet at the terminal rate. Demand reduction has to contribute, along with other measures, to lowering the current account deficit. A firm monetary policy reaction to inflation exceeding tolerance bands helps anchor expectations. The repo rate has to rise more. But should the rise be taken upfront or staggered over time? We examine the arguments for and against frontloading.

When behaviour is forward-looking front loading can pre-empt inflationary pressures. But if lagged effects of monetary policy are large, as in India, over-reaction can be very costly. Harmful effects become clear too late and are difficult to reverse. Gradual data-based action reduces the probability of over-reaction. Taking Indian repo rates too high imposed heavy costs in 2011, 2014 and 2018. A credit and investment slowdown was aggravated and sustained. It is necessary to go very carefully now that forward-looking real interest rates are positive.

Statement by Prof. Jayanth R. Varma

I wrote in my August statement that further withdrawal of accommodation is warranted beyond the rate increase in that meeting. However, I also indicated that we may be beginning to approach the terminal repo rate. My view remains largely the same today, and based on this, I think the MPC should now raise the policy rate to 6 percent and then take a pause.

46. A pause is needed after this hike because monetary policy acts with lags. It may take 3-4 quarters for the policy rate to be transmitted to the real economy, and the peak effect may take as long as 5-6 quarters.

United States

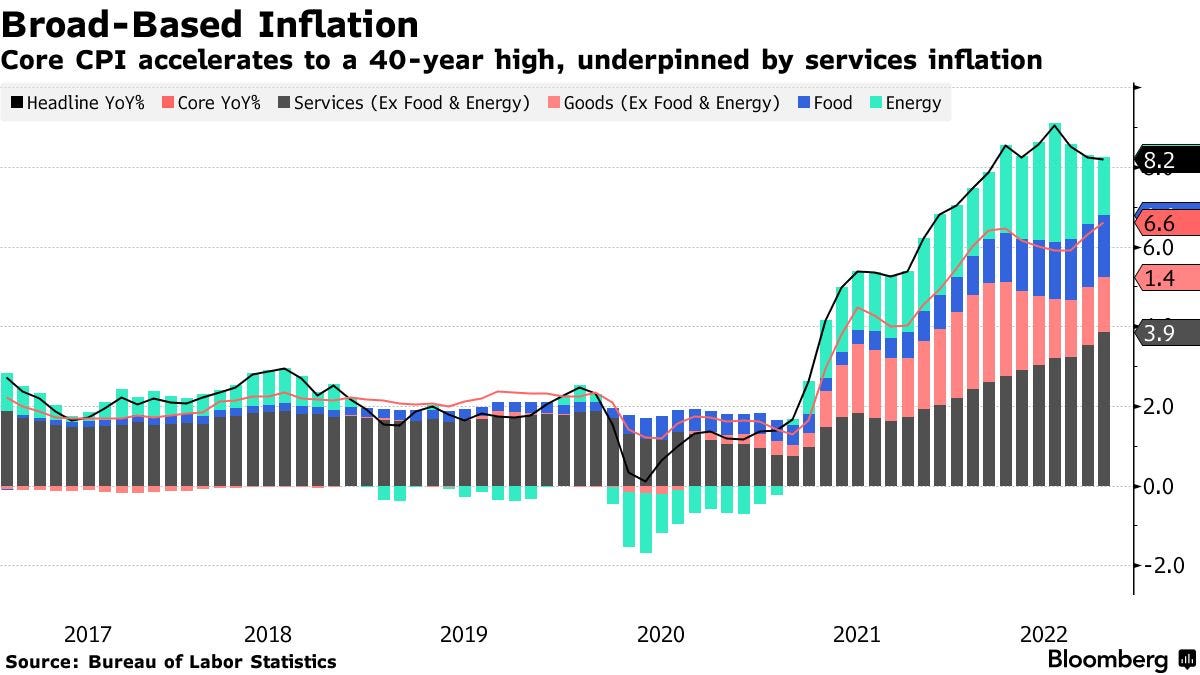

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation fell slightly to 8.2% YOY in September from 8.3% in August.

The rise in inflation was driven by rising transportation costs, medical costs, food, and rents. Energy prices continued to oderate.

Inflation is now switching from goods to services.

But core inflation, excluding food and energy, rose to 6.6% from 6.3%. This indicates the stickier elements.

Why does U.S. inflation matter?

When U.S. inflation was low, U.S. interest rates remained low. So life was relatively easier for emerging markets because they didn’t have to worry about the U.S. But now that inflation is rising in the U.S., the Fed has started hiking rates.

But you might be wondering, why are we and everyone else so preoccupied with what happens in the U.S., and how does it affect India?

In a way, the U.S. monetary policy is a global monetary policy because it affects the rest of the world through various channels. Silvia Miranda-Agrippino and Hélène Rey published a brilliant paper on how the U.S. monetary policy affects the rest of the world. Here are a few excerpts:

We find evidence of powerful financial spillovers of US monetary policy to the rest of the world. When the US Federal Reserve tightens, domestic demand contracts, as do prices. The domestic financial transmission is visible through the rise of corporate spreads, the contraction of lending, and the sharp falls in the price of financial assets, such as housing and the stock market.

But, importantly, we also document significant variations in the Global Financial Cycle, that is, the shock induces significant fluctuations in financial activity on a global scale. Risky asset prices, summarized by the single global factor contract very significantly. This is accompanied by strong deleveraging of global banks both in the US and Europe, and a surge in a measure of aggregate risk aversion in global asset markets.

The supply of global credit contracts, and there is an important retrenchment of international credit flows that is particularly pronounced for the banking sector. International corporate bond spreads also rise on impact, and significantly so. These results are consistent with a powerful transmission channel of US monetary policy across borders, via financial conditions. The contraction of domestic credit and international liquidity that follows the US monetary policy tightening is confirmed also for the subset of countries that have a floating exchange rate regime.

Inflation leads to more inflation

The other big reason why everyone is freaking out over inflation is that once inflation becomes entrenched, it can stay there for a long time.

The reason why pretty much the entire world is tightening is because of the reasons I mentioned above:

When U.S. inflation increases, it’s exported to the rest of the world through a strong dollar.

If inflation becomes sticky, it takes a long time for it to come down. This is the worst-case outcome that policymakers and central banks want to avoid at all costs.

Central banks, especially the Fed, are ok with crashing the economy and causing unemployment than allowing high inflation to become sticky. Given a choice between overreacting and underreacting, most central banks, at this point, would prefer to overreact.

What’s causing this inflation?

You might also be wondering where is all this inflation coming from. The European Central Bank (ECB) and Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco published some research recently. The data shows that a bulk of the inflation is due to supply-related issues like supply chain issues, labor shortages, production delays, raw material shortages, etc.

Decomposition of European inflation

Decomposition of U.S. inflation

The issue is that interest rates are a blunt tool. Raising interest rates won’t magically fix the supply chain, create more raw materials, and fill job vacancies. This is the conundrum central banks today are facing. Monetary policy alone isn’t an answer to everything.

IMFs gloomy outlook for the global economy

The International Monetary Fund published its Global Financial Stability Report earlier this week, the report provides an assessment of the global financial system and markets. And the IMF didn’t have a pretty picture to paint.

The IMF downgraded the global growth forecasts for the 4th time this year. The global economy is projected to grow by 3.2% in 2022. The growth forecast for 2023 has been cut by 0.2% to 2.7%.

To quote Tobias Adrian, the financial counsellor and director of the monetary capital department of IMF:

The global environment is fragile with storm clouds on the horizon. Inflation is now at multi-decade highs and broadly spread across countries. The economic outlook continues to deteriorate in many countries.

IMF hosted a press conference after releasing the report, below are some of the key insights from the IMF speakers, Tobias Adrian, Financial Counsellor and Directorate of the Monetary Capital Markets department, Fabio Natalucci, Deputy Director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department, and Antonio Garcia Pascal, who is Deputy Division Chief in the Monetary and Capital Markets Department.

On current global financial stability

The global financial stability risks have increased with the balance of risk skewed to the downside amidst the highest inflation in decades.

Due to extraordinary uncertainty, markets have been extremely volatile with sharp declines in risk assets such as equities and corporate bonds. Deterioration in market liquidity has also led to amplified price moves.

Financial conditions in many advanced economies are now tight by historical standards and in some emerging markets, they have reached levels last seen during the height of the COVID-19 crisis with conditions worsening in recent weeks.

Rising interest rates, worsening fundamentals, and large outflows of capital have pushed up borrowing costs in emerging markets. This impact has been severe for more vulnerable economies where 20 countries are either in default or trading at distressed levels. Unless there is an improvement in market conditions, there’s a risk of further defaults in frontier markets.

As per the IMF’s Global Stress Test for banks, in a severe downturn scenario, 29% of the Emerging Market banks could breach minimum capital requirements and corporate credit also faces an increased risk of default.

As per Fabio Natalucci, we are essentially seeing a slight regime shift in terms of macro, where we move from a low inflation environment with low rates and low volatility to an environment where inflation is higher.

Investors need to readjust the way they do asset allocation and the way they think about risk and liquidity.

On India's financial stability situation

Monetary policy has tightened in India, similar to other Emerging Markets, and the IMF expects further tightening of monetary policy going forward.

In terms of financial stability, there are some preexisting vulnerabilities, both in the banks and in the nonbanking system, in India, which are a cause of concern.

On the banking side, the issue is related to prudent underwriting standards to have adequate and build further capital. It is important to recognize problem loans, if they are left on the balance sheet, it can be a drag to future lending and the recovery of the banking system. This IMF sees as the key issue.

On the recent instability in the UK financial markets and its effects

The announcement of the UK government’s new plan in terms of fiscal expenditure triggered a rise in interest rates which is expected from a change in fiscal policy but some of that rise has been disorderly leading to a sharp and quick increase in yields threatening financial stability. The Bank of England stepped in with targeted and temporary asset purchases to arrest the increase in yields at the longer end of the guilt market.

At this point, the IMF doesn’t anticipate the Bank of England's actions being necessary for other countries, but they do flag many vulnerabilities in financial markets, so there is a tail risk that financial instability could occur in other countries.

Now there is leverage in many countries around the world and many segments of the market, in particular in the nonbank financial system. There are maturity mismatches, liquidity transformation, and hidden leverage; so there could certainly be financial stability problems and market dysfunction in other countries as well.

The sub-financial stability assessment in the UK was published in February of this year and included recommendations for better data and better regulation of risk-taking in the non-bank financial system. IMF did a financial sector assessment in the U.S. as well and flagged that the non-bank financial system has pockets of risk. There are a number of vulnerabilities in the non-bank financial sector that have been building over the past decade.

Inflation, rising interest rates and the rising dollar

Central banks must act resolutely to bring inflation back to target, to keep inflationary pressures from becoming entrenched, and to avoid de-anchoring of inflation expectations. Clear communication about the policy function is crucial to avoid unwarranted market disruptions.

The US Federal Reserve has been increasing interest rates in order to get inflation back to its 2% inflation target. The IMF views the path of interest rates in the US as appropriate and the tightening in the US as the appropriate step to achieve the objectives of the Federal Reserve.

Along with the US, other countries are also changing their stance on monetary policy. Many countries around the world are also tightening monetary policy. There are certainly spillovers of the tightening resulting in a stronger dollar.

Some of the exchange rate movements are driven by the differential stance of monetary policy. Then there are trade shocks in many economies, such as Europe where the imports of energy, oil, and gas from abroad that has tended to put depreciation pressures on the Euro.

There is a debate around the level of the target for inflation but it is important to know that most emerging markets have high inflation as well so a tighter stance of policy and tighter financial conditions is actually appropriate for many emerging markets.

Monetary policy is always conditional on economic developments, so there could be inflation surprises to the upside. There could be worse-than-expected prints for real activity, and there could be a variety of other shocks globally. Over time, however, monetary policy would always take those shocks into account and readjust what the optimal path is going forward.

This is a new world. We are going to face higher rates and high inflation probably for a while.

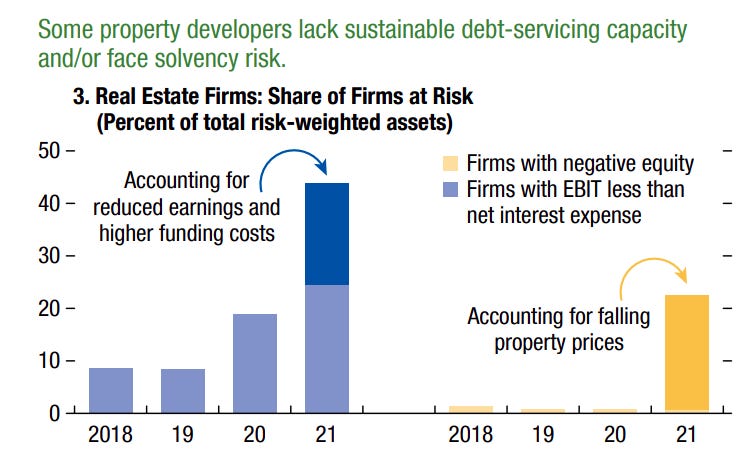

On the Chinese property sector crisis

There has been stress in the Chinese property market compared to recent years. The growth rate in China has been declining to some degree, and that is one contributing factor to the slowing of the property market.

There has been a lot of investment in properties over many years which has also led to a demand and supply imbalance in some regions in some cities.

While policymakers in China are focused and taking necessary policy steps, there is the potential for more turbulence. There is the potential for exposure to the banking system or to the market-based financial system.

As per IMF, the liquidity issue in the property development sector is turning into a solvency issue, and if the earnings decline crystallizes, 45% of the property developers will be unable to meet interest payments with earnings.

You can download the IMF Global Financial Stability Report here, and watch the press conference here 👇

On TradingQnA

Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of India released minutes from its Monetary Policy Committee meeting held from September 28th to 30th 2022. Here’s a summary from the MPC meeting👇

Summary of the 38th RBI MPC Meeting

🐦 On Twitter

📖 Reading Recommendations

That’s it from us today. Hope you loved reading the latest issue, do let us know your views in the comments section below. And do like and share 😃

If you have any queries related to trading, investing or anything related to stock markets, post them on our forum.

For more, follow us on Twitter: @Tradingqna