Thank you for all your love, starting with this issue, Markets and Macros will also be available in Hindi 😀 You can read the Hindi version here.

Hello folks, welcome to the latest issue of Markets and Macros by TradingQnA. In this issue, we take a look at;

Big tech in financial services

Global hunger crisis

Money, war and changing world order and more…

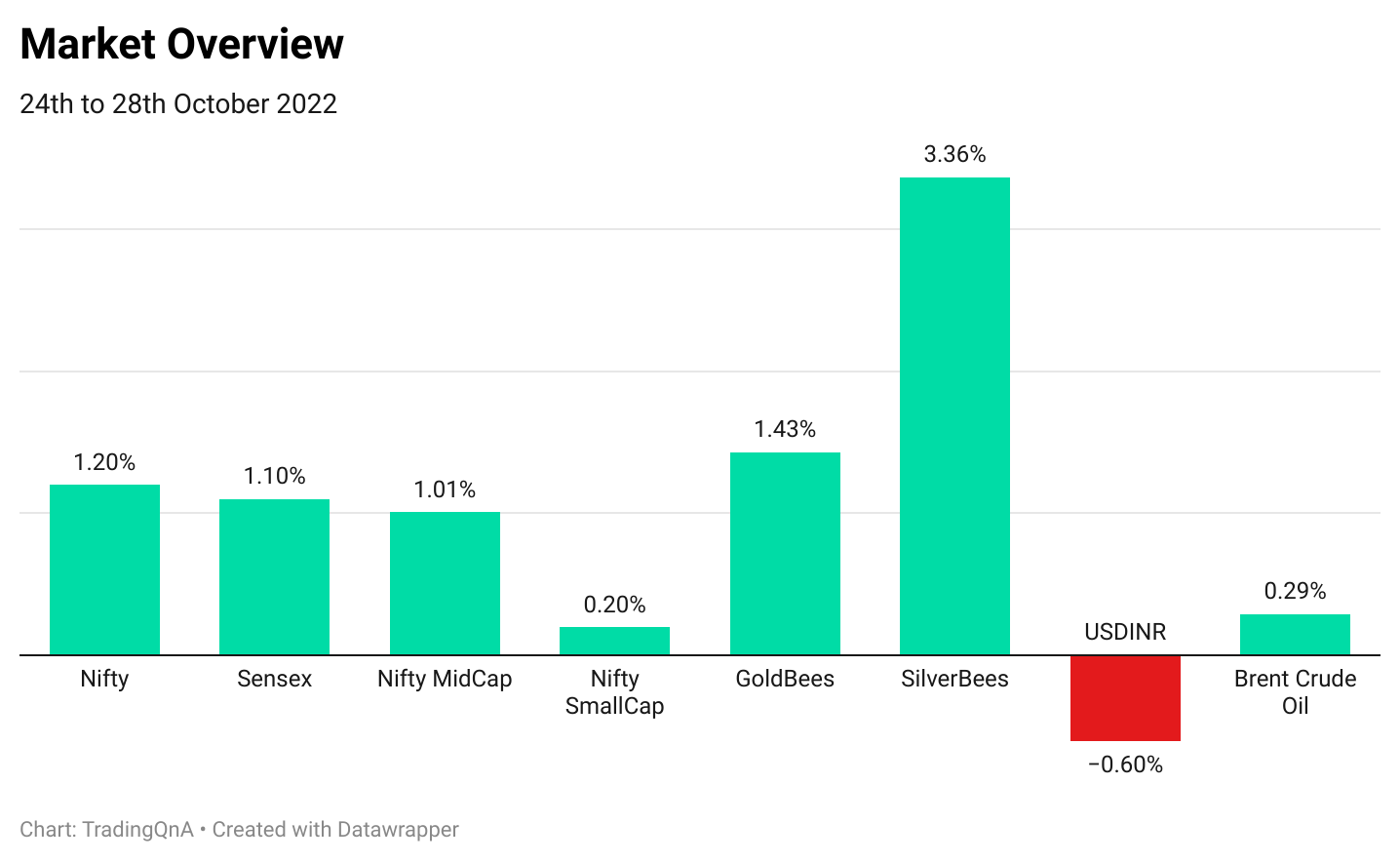

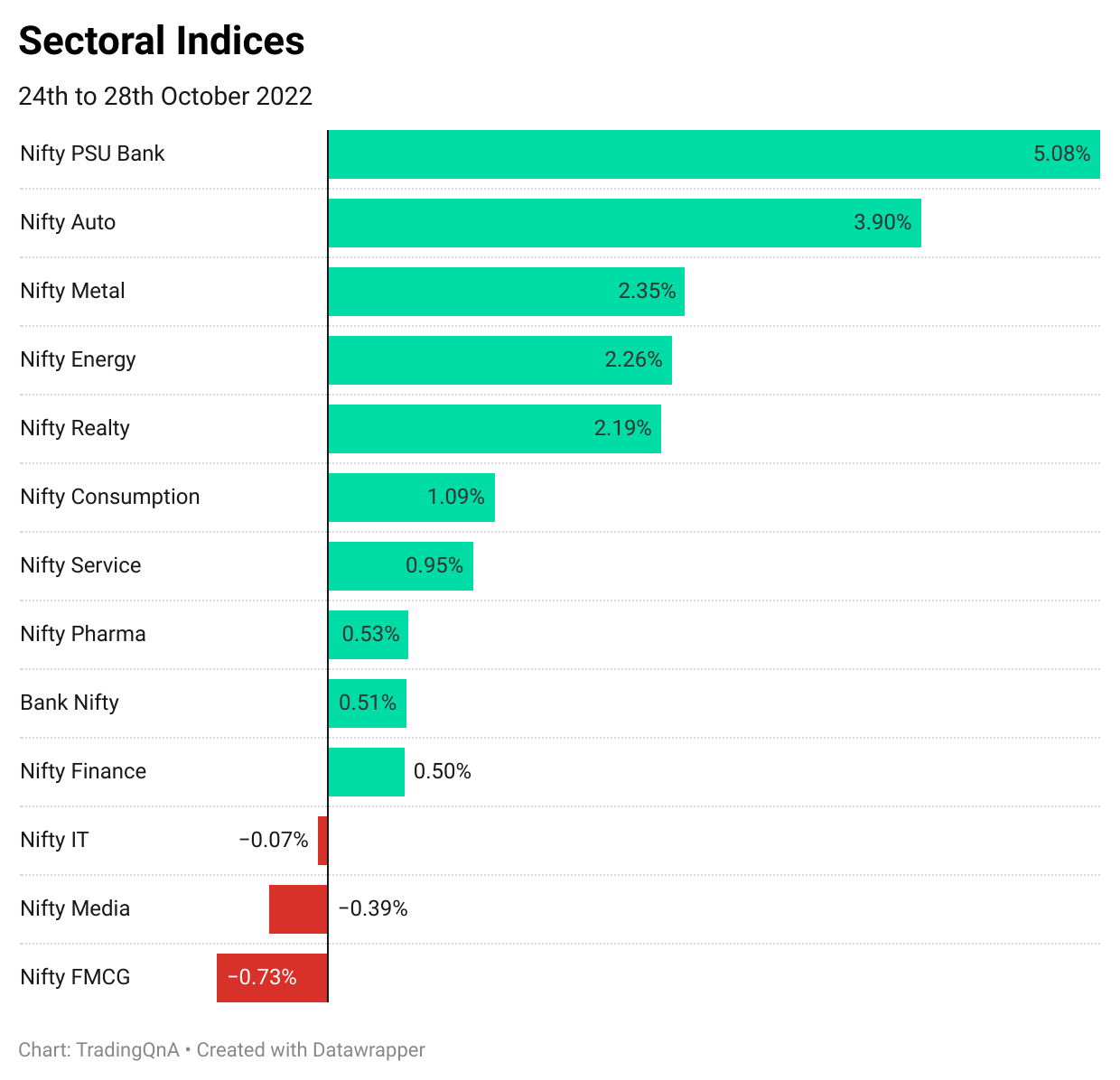

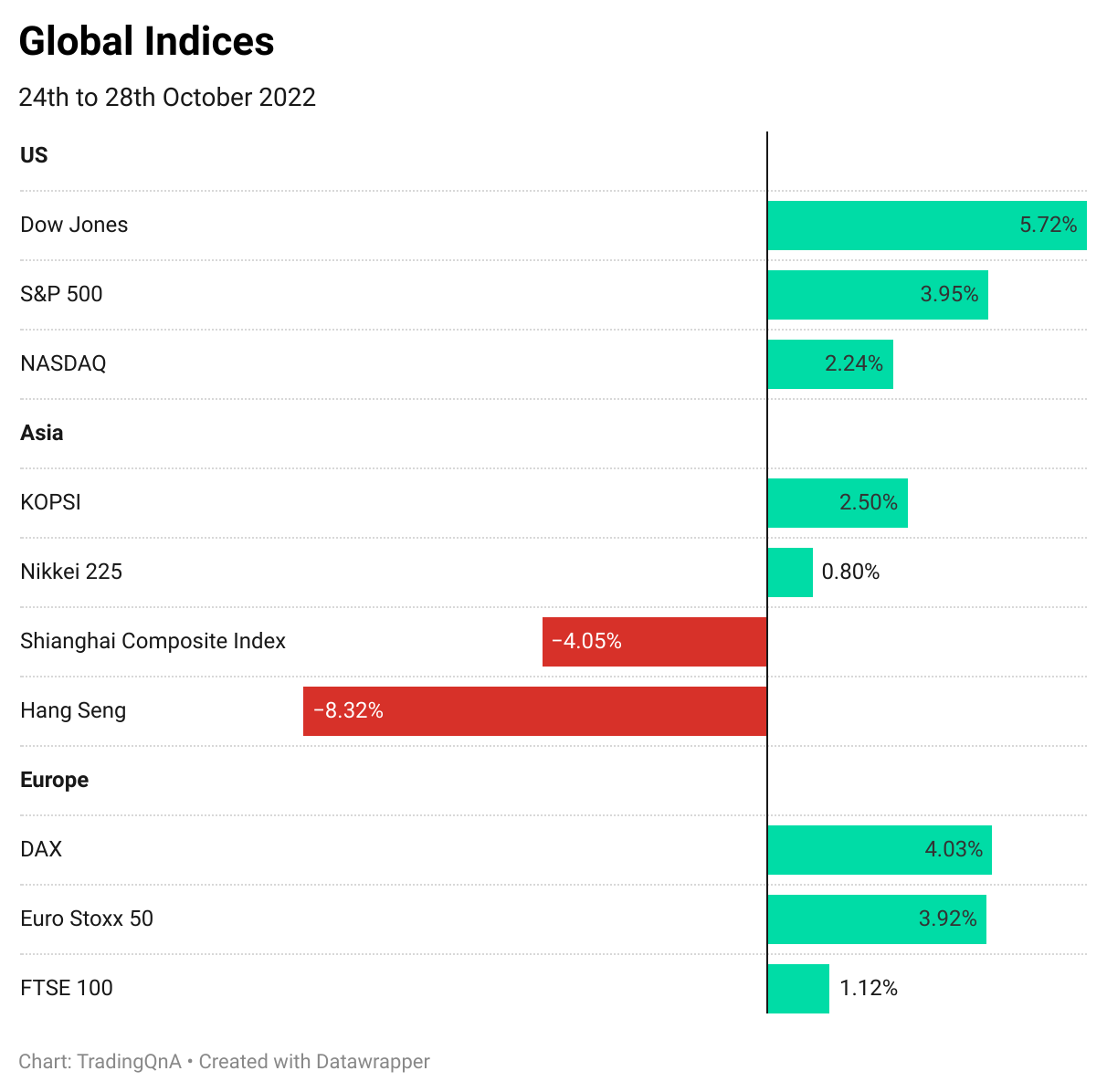

Weekly Market Wrap

Here’s how the markets fared in the week ended 28th October;

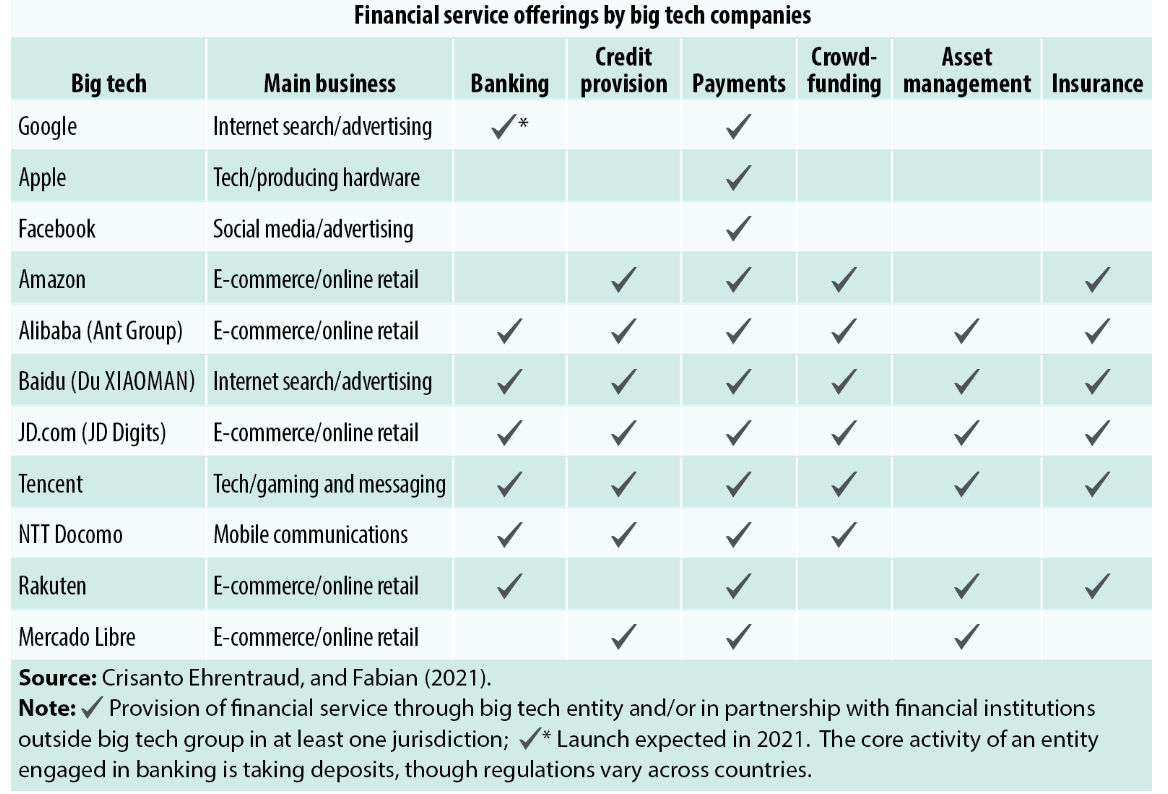

Big Tech in financial services

Big Techs such as Google, Facebook, Alibaba, Tencent and Amazon are increasingly coming under regulatory scrutiny around the world. But before that, how did big tech end up in financial services?

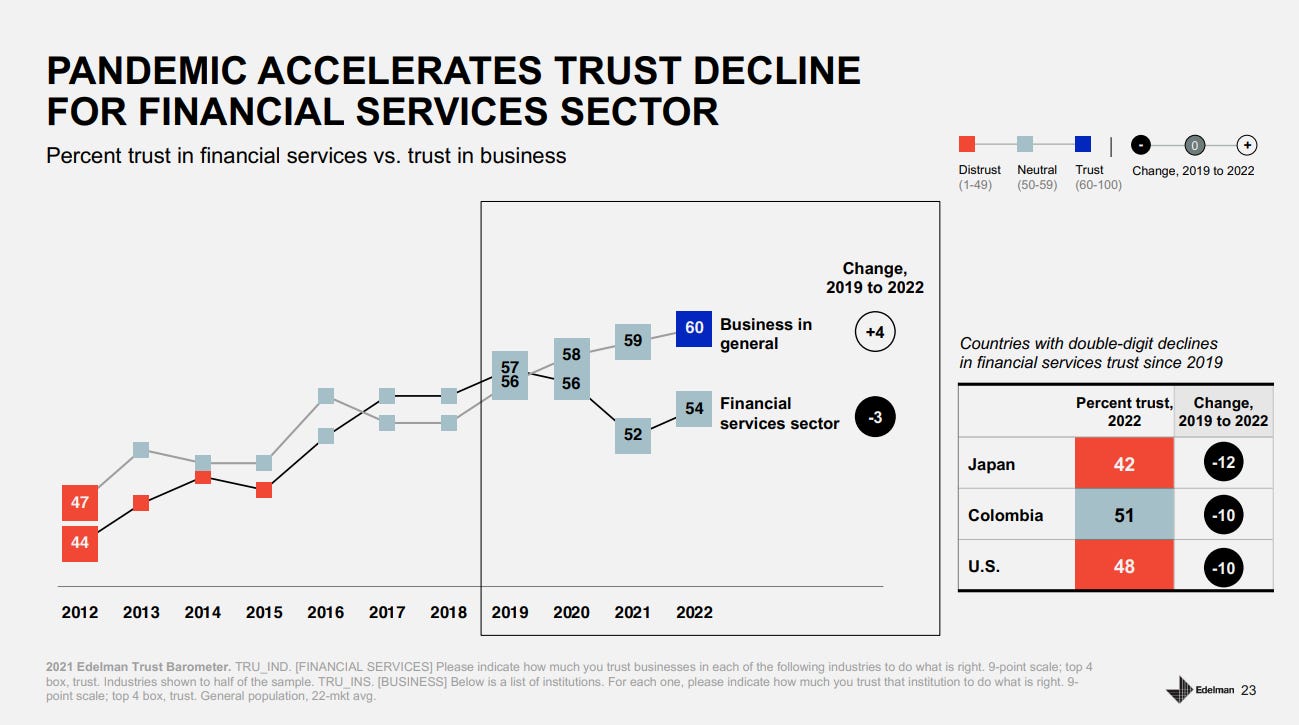

While globalization seems to be retreating, it’s not the case with financial globalization. The global financial system is more interconnected than ever. One of the fallouts of the 2008 crisis was the tremendous loss of faith in financial institutions–especially the banks–around the world. Banks never recovered.

(Source: Edelman)

In the aftermath of the crisis, regulators around the world introduced new regulators that forced banks to retreat from a lot of financial activities. These two factors, loss of trust and tighter regulations led to the entry of new fintechs, asset managers and private equity firms in finance.

(Source: IMF)

Nowhere is this more apparent than in China, where internet giants such as Alibaba and Tencent are not just the largest e-commerce and media companies, but also the largest financial services companies. For example, Yu’e Bao–a money market fund run by Alibaba at one point, had over $200 billion in assets.

There are both positives and negatives to the entry of big techs into finance. The positive is that they can offer financial services at cheaper costs and can innovate faster than the incumbents. But they also pose financial stability risks.

What does this mean?

Big Techs operate in grey areas where they perform the function of banks or other regulated entities without being regulated. For example, most fintech lending apps today aren’t regulated by RBI, but they’ve built huge lending operations. We also saw how this could go wrong with the Chinese lending apps saga.

These are challenges that regulators face. They need to take into account the unique features of Big Techs—their vast scale, huge customer bases and access to large amounts of data—and reduce risks from the interconnection among different financial entities. For example, what are the risks of apps like Google Pay processing loans without having a banking license through other banks and NBFCs?

So, what are regulators doing? There’s been a lot of research on the topic and coincidentally, there was an interesting research paper in the October 2022 RBI bulletin. I read through them all so that you don’t have to.

The regulatory initiatives can be covered under the following dimensions:

1. Ensuring competition by limiting the dominance

Big techs can leverage their huge customer bases to force exclusivity when partnering with other financial service companies. This gives them an unfair competitive advantage.

The traditional approach of fixing things after something has gone wrong may not work. Regulations that focus on preventing harm and entity-based regulation is the need of the hour.

For example, in the US, EU and China, we’re seeing a shift from regulators having to prove market dominance (market power) to an approach where firms have to prove that a merger will not lead to a dominant market position. The Digital Markets Act (DMA) in the EU will regulate the activities of market gatekeepers by not letting them impose unfair conditions on businesses and consumers.

2. Securing data protection and data sharing

Big Techs with the vast data they have, offer tailored financial services to people without credit history or collateral, which leads to people relying on predatory lenders.

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) levies harsh fines for violating its privacy and security standards. Several countries’ data protection regimes are now doing the same.

The “purpose specificity” and “security requirements” under GDPR are relevant to Big Techs:

Purpose Specificity: User’s data is utilized only for the purpose consented to by them.

Security Requirement: Confidentiality and availability of users’ data have to be protected.

The Digital Services Act (DSA) also protects users from any misuse of their data.

3. Tracking Business Conduct

Big Techs offer services like payment, banking and insurance etc. as bundles, through subsidiaries and joint ventures with banks. In China, Tencent owns 30% of WeBank. While in India, Google Pay offers health insurance, in partnership with SBI General Insurance.

Entities with a banking/insurance license are regulated individually, but Big Tech groups are not regulated on a consolidated basis. Multiple regulators operate in silos and some aspects slip through the gaps. Can we have a single regulator for entity-specific guidelines? Maybe. Till then, broader guidelines are required.

For example, in the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) specifies guidelines for payment institutions and requires clear details on the group structure. Coincidentally, the FCA is launching an inquiry into Apple, Amazon, Google and Meta’s entry into retail financial services.

4. Monitoring operational resilience

Do you use Google Pay? It has made life convenient, hasn't it? Now imagine if it fails. The impact that it, and similar apps, can have on financial activity is quite intuitive to figure.

Big Techs provide services and infrastructure (e.g. cloud computing and data analytics) to the financial system. Any failure creates a significant impact. Something that bothers us is the way that these services have been integrated into our financial system. Have they become ‘too critical to fail’? How to ensure that it doesn’t happen?

Well, the existing regulations cover only entities executing these activities instead of the whole group. Any disruption in a group company can trickle down to others. Thus, new regulations to address operational risks are being devised:

In the EU, the proposed Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) ensures that firms need to withstand and recover from all types of ICT-related disruptions and threats.

In China, the Financial Holding Companies (FHC) framework requires that all FHCs create a risk management system to monitor operational and IT risks.

US regulators oversee firms that are significant third-party service providers to banks.

How is India planning to regulate Big Tech?

India requires local storage of payments data and is legislating a data protection law.

RBI has issued draft guidelines to ensure the management of the risks in outsourcing of IT activities. It has also recently introduced digital lending guidelines.

The Government is also deliberating regulating Big Tech’s data collection and usage policies.

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Commerce tabled a report in Rajya Sabha in July 2022 recommending an ‘ex-ante’ (regulating before) approach to regulate competition in the digital market economy instead of the ‘ex-post’ (regulating after something has happened) model followed now.

A code of conduct on data will regulate companies acting as gatekeepers, ensuring that data is used only to serve the consumer’s interest. Though this report is for regulating e-commerce, it will impact the provision of financial services by Big Tech as well.

Recently, the RBI governor, Mr Shantikanta Das, addressed the 2020 BFSI summit and said:

“The provision of financial services through the digital channel, including lending through online platforms and mobile apps, have brought in issues relating to unfair practices, data privacy, documentation, transparency, conduct, breach of licensing conditions, etc. The Reserve Bank will soon issue suitable guidelines and measures to make the digital lending ecosystem safe and sound while enhancing customer protection and encouraging innovation.”

It will be interesting to see how these guidelines/legislations to regulate Big Tech will shape up and we will keep you updated.

— Written by Abhinav

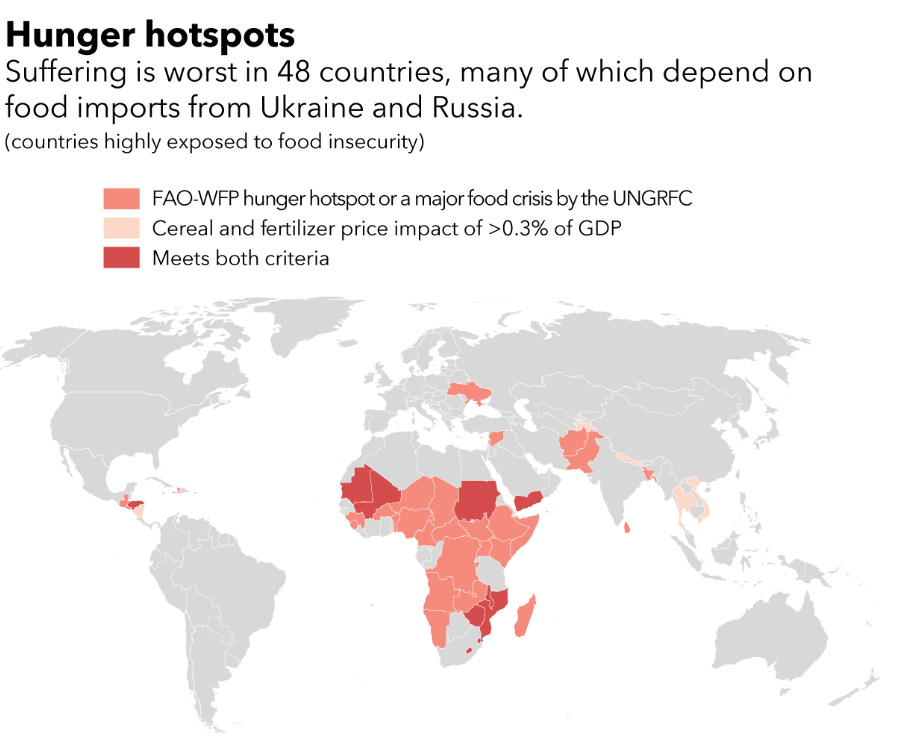

Global Hunger Crisis

We are facing the largest food crisis in modern history. 828 million people sleep hungry every night and 355 million face acute food insecurity. As per an IMF paper, $5-7 billion is required immediately, plus another $50 billion over the next year to end acute food insecurity.

Climate shocks, regional conflicts and the pandemic have disrupted food production and distribution. Countries relying on food imports are crippled by high interest rates, a soaring dollar and elevated commodity prices. For example, in Ghana, the local currency Cedi has lost 44% this year against the dollar, the situation is dire.

Though global food commodity costs have fallen for six straight months the rising dollar has negated the effect. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) states that this year’s global food import bill is at a record high.

IMF estimates that higher import costs for food and fertilizers will add $9 billion to balance of payments pressures in 2022 and 2023.

Who is hit the worst?

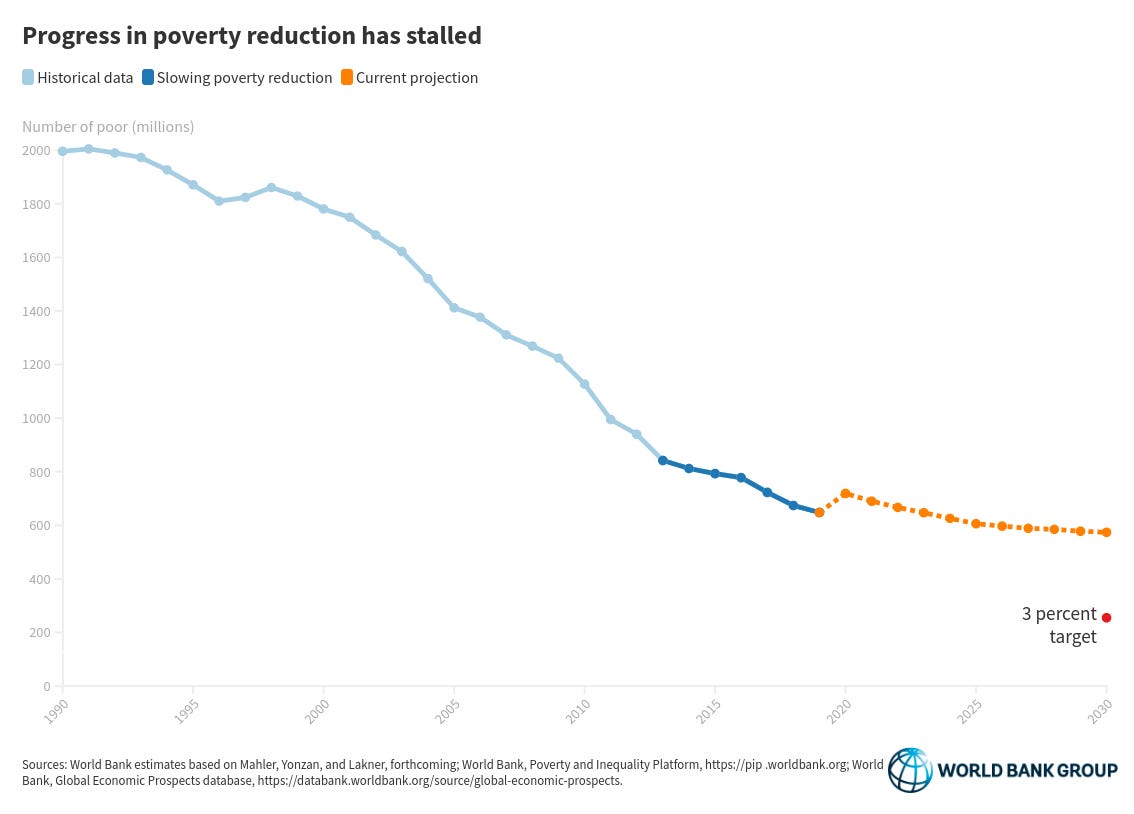

A World Bank paper states that extremely poor people spend two-thirds of their resources on food. According to this World Bank report, the pandemic stalled global poverty reduction and added over 18 million on top of the estimated 667 million poor in 2022.

How did we get here?

As Russia invaded Ukraine, headlines about a global wheat shortage appeared, and we saw illustrations like the following:

(Source: IMF)

The disrupted Black Sea supply chain hampered food security, but was there a global shortage of food? We don't think so. Bumper crops in India, Australia and elsewhere meant that there was enough food, we just didn't move it properly. Speculation and war-induced trade restrictions exacerbated the problem.

Why are we facing this problem?

Well, large-scale industrial agriculture has made poorer countries dependent on imports, and they can’t feed themselves when global trade falters. Dr. Sarah Taber, a crop scientist, says that subsidies and markets like biofuels distort global food systems.

They promote overproduction and flood markets with cheap food, undercutting small farmers. During shortages, these overproduction policies paradoxically make people hungry. Even though there’s enough food, it simply flows to feedlots and fuel tanks rather than to hungry people. Simply put, the international food trade limits importing countries’ ability to build their own food systems.

Can we ensure this doesn't happen?

Mechanized agriculture is important, arguably in grasslands, it is the most effective method of food production. But to feed the world sustainably we have to diversify beyond a few regional breadbaskets such as the Black Sea, the North American grain belt and Brazil’s soy-producing states.

Agroforestry is a viable option for large-scale food production. This is not even a new idea. Chestnut trees grew in the Appalachian region (Eastern US) which is a hilly terrain that industrial agriculture considers unfarmable. There were 3-4 billion trees before a fungal disease caused near extinction in the 20th century. These forests could yield around 3-4 trillion calories per year, or enough to provide for twice the US population.

Another solution is fisheries. Countries like Somalia, Yemen, Lebanon and Algeria which are dependent on food imports have coastal fisheries. Centuries of pollution and unmanaged fishing have ruined them. Revival of sustainable aquaculture can bolster food security for arid coastal nations.

Seaweed farming can provide food or industrial feedstocks. Instead of polluting watersheds like land crops, seaweed removes excess nutrients and oxygenates the water. This rehabilitates the environment and strengthens fisheries. Seaweed removes enough CO2 from seawater to counteract acidification allowing corals and shellfish to thrive. These shellfish can be cheap, abundant and non-polluting sources of protein.

Where do we get the funds to execute this?

Well, for starters, the World Bank Group is making up to $30 billion available over a period of 15 months in areas such as agriculture, nutrition, water and irrigation.

Beyond that, we need political leadership that responds to the need for a resilient food system. The first step towards this is spreading awareness about the root causes of the food crises, something that we have tried to contribute to.

— Written by Abhinav and Esha

Money, war and a changing world order with Debashish Bose

We are at an important crossroads in history. The pandemic might seem like it’s behind us but we have a raging war in Europe, unprecedented sanctions, currency crises, inflationary pressures, and volatile markets. There are early signs of a shift away from the dollar and uncertainty about the US-led global order.

So what does all this mean for India and the world? We caught up with Debashish Bose, Managing Director—Public Equities at Oaks Asset Management, to make sense of it all.

In this conversation, Debashish talks about:

1. How money is created in the modern world

2. The geopolitical divide

3. Fall of Yen and Japan’s currency conflict

4. Limited power of central banks

5. Cracks in the current dollar-dominated system

6. Advice for investors and much more

You can watch the full conversation here 👇

📖 Reading Recommendations

Why Japan Stands Virtually Alone in Keeping Interest Rates Ultralow

The yen is in free fall. Inflation by some measures is the highest in decades. And conventional wisdom says a rate increase could ease both problems. But the Bank of Japan — never one to follow the crowd — has remained steadfastly committed to its ultralow interest rates, arguing that making money more expensive now would only suppress already weak demand and set back a fragile economic recovery from the pandemic.

Continue reading…

The Crypto Story - Matt Levine

You might like it or not, but Cryptocurrencies have certainly managed to attract the attention of people all around the world like anything else. In this piece, Matt Levine deep dives into the story of Crypto—Where it came from, what it all means, and why it still matters.

Continue reading…

An explainer on India’s battle with affordable housing

In 2015, the Indian government debited the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana scheme with the goal to make affordable housing accessible to the most economically vulnerable people in rural and urban areas, through the scheme the government intended to offer every Indian family a brick and cement house with gas, water, electricity, and a toilet by the year 2022.

So where do we stand now? Finshots takes a look in this story.

Continue reading…

🎧 Listen to

— Curated by Abhinav and Shubham

That’s it from us today. Hope you loved reading the latest issue, do like and share this with your friends and let us know your views in the comments section below.

If you have any queries related to trading, investing or anything related to stock markets, post them on our forum.

For more, follow us on Twitter: @Tradingqna

sir you can not upload last week article, dont break consistency

sir, please share articles on weekend days